Riparian and Creek Ecosystems (RI) and (CK)

In the Discovery Islands

• Riparian ecosystems occur along flowing freshwater (creeks) and around the still waters of lakes and ponds and wetlands. Riparian ecosystems are usually narrow and linear. Creeks are separate aquatic communities that have complex inter-relationships with the Riparian ecosystems on their border.

• Riparian ecosystems are constantly changing due to seasonal fluctuations and other effects of freshwater movement, including flooding and exposure, partial drying, erosion, siltation and debris accumulation. Their typically moist soils support distinct plant communities, usually including a lush understory of shrubs and herbs, and flood-tolerant deciduous and coniferous tree species.

• Creeks result from water run-off that is channelled by the underlying geology. Although they are subject to seasonal fluctuations, creeks are home to fish, numerous invertebrates, and various aquatic or semi-aquatic plants.

DIEM has mapped Riparian and Creek Ecosystems together and moss green in the Sensitive Ecosystems Mapping, with creeks represented as lines on top of the riparian which is mapped as the area around the creek.

DIEM has mapped Riparian and Creek Ecosystems together and moss green in the Sensitive Ecosystems Mapping, with creeks represented as lines on top of the riparian which is mapped as the area around the creek.

The same Creek may cascade and flood, or pool and trickle, due to more or less precipitation The flow and course of a creek are also affected by seepage and evaporation, animals (especially beavers), and debris deposition or movement. Creeks provide a local water source, as well as delivering water for riparian and other downstream ecosystems

Riparian Ecosystems are influenced by their adjacent freshwater – and they always surround creeks, ponds, lakes and wetlands. Riparian zones can also occur atop gravel bars, spread over floodplains, in forest gullies where seepage occurs, and as micro-areas in the sprayzone of cascading water. The high variability and long edge of riparian ecosystems provide food, water and shelter that support many species and interactions that result in high productivity and biological diversity. Although natural disturbances are frequent in riparian ecosystems, the roots of riparian vegetation help bind soils and stabilize the edges of moist areas. Riparian vegetation and soils also play a key role as natural water filtration systems and help to regulate the flow and the temperature of fresh waters. The form and size of a riparian zone is determined by the shape and size of surrounding terrain.

Riparian Ecosystems are influenced by their adjacent freshwater – and they always surround creeks, ponds, lakes and wetlands. Riparian zones can also occur atop gravel bars, spread over floodplains, in forest gullies where seepage occurs, and as micro-areas in the sprayzone of cascading water. The high variability and long edge of riparian ecosystems provide food, water and shelter that support many species and interactions that result in high productivity and biological diversity. Although natural disturbances are frequent in riparian ecosystems, the roots of riparian vegetation help bind soils and stabilize the edges of moist areas. Riparian vegetation and soils also play a key role as natural water filtration systems and help to regulate the flow and the temperature of fresh waters. The form and size of a riparian zone is determined by the shape and size of surrounding terrain.

In the Discovery Islands, there are three distinct types of Riparian Zone: BENCH FLOODPLAINS are adjacent to watercourses, and are graded according to the amount of flooding. Low benches are flooded at least every other year for extended periods during the growing season. High benches have subsurface flows within the root zone of plants for extended periods, but only periodic brief flooding of the ground surface. FRINGE describes the narrow edge of water courses or water bodies with no floodplain. Plants receive regular subsurface flooding of root zone. GULLIES AND CANYONS are steep V- or U-shaped creek beds with minimal flooding, but influenced by water due to proximity and exposure on steep sides; they may have unique microclimate.

WHEN YOU EXPLORE creeks and riparian areas, try not to disturb banks and roots, as this weakens the soils and dislodges sediments into the water. And be careful if you walk on the creek bed: you’ll likely be disturbing sediment, fish eggs and fish, and you may crush other animals and their eggs or larvae.

Look For Typical & Rare Species in Intertidal Ecosystems

Note: Riparian and Creek ecosystems share many species that live in and around both of these more-or-less moist ecosystems.

TYPICAL FAUNA American dipper, common merganser, common yellow-throat, little brown bat, Lorquin’s admiral, MacGillivray’s warbler, mink, northern-red-legged frog, river otter, rough-skinned newt, Swainson’s thrush, yellow warbler, western toad, northwestern salamander. Aquatic species: Caddis fly larvae, Coho salmon, cutthroat trout, freshwater lamprey, stickleback, water strider, and whirligig beetle

TYPICAL FLORA Big-leaf maple, bitter cherry, black cottonwood, black hawthorn, cascara, coastal leafy moss, devil’s club, goat’s beard, lady-fern, maiden-hair fern, oak fern, Pacific crab apple, red alder, red-osier dogwood, Pacific ninebark, salmonberry, sitka spruce, skunk cabbage, stinging nettle, water parsley, vine maple, western hemlock, western red-alder, western red-cedar, willow species, American bulrush, slough sedge, small-flowered bulrush

SPECIES AT RISK northern red-legged frog (Blue, Special Concern),western toad (Blue, Special Concern), great blue heron (Blue, Special Concern), cutthroat trout (Blue), grizzly bear (Blue, Special Concern), white adder’s-mouth orchid (Blue), pointed rush (Blue),

ECOLOGICAL COMMUNITIES AT RISK western redcedar/Sitka spruce/skunk cabbage; black cottonwood/red alder/salmonberry; Sitka spruce/salmonberry; western redcedar/swordfern

*For comprehensive species lists & rarity explanation, click here.

Some Observations of Local Species

Caddis flies

They favour cool running water and are an important food source for fish, especially salmon and trout. Their larvae build homes around themselves out of whatever small materials are available. They emerge in summer as flies, living for only two to eight weeks before laying eggs in the gravel on a creek bottom.

Caddis fly larvae

Caddis fly larvae favour cool running water and build homes around themselves out of whatever materials available. They eat small animals and plants and are important food for fish. They emerge the following summer and live as flies for 2 to 8 weeks.

Common water striders

Common water striders feed, on the surface of the water, on living or dead insects that they grab with their short front legs. They don’t have wings but move quickly, as fast as 1 m/sec, so as not to be eaten themselves. They walk on the water by virtue of their out-stretched weight distribution and fine hairs that trap air and increase their surface area.

Whirligig beetles

They are scavengers, usually at the surface although they can dive and also fly off to new creeks and ponds. When diving they carry a bubble of air with them to breathe. Their eyes are divided allowing them to see both above and below the surface. Their erratic swimming helps with predator avoidance and seems important in their gregarious social interaction. They secrete a milky secretion with an unpleasant odour when caught.

Lorquin’s admiral butterflies crop

They are linked to riparian areas by their choice of black cottonwood as one of their favoured larval food-plants. Other foods include willow, crab apple, bitter cherry, hawthorn and other shrubs often found on the borders or wet areas. These shrubs also supply abundant flowers and nectar for the adult butterflies.

Little brown bats

Little brown bats, formerly the most common bat in coastal forests, are disappearing throughout much of North America due to white-nose disease syndrome. Both summer maternal colonies and winter hibernacula are important habitats to protect. They are classified as endangered although still fairly common in BC.

Macgillivray’s warblers

They breed in thick shrubby areas, usually preferring the riparian edges of coniferous forests. While still abundant their populations across BC and Canada have been decreasing.

Mink

Mink, like coastal otters use both the coast and riparian areas as their major habitat. Still important to the fur trade, mink are also an important link in the food chain controlling populations of small mammals, invertebrates and coastal crustaceans. They have dens along the coast and they and their sign can be seen along shorelines.

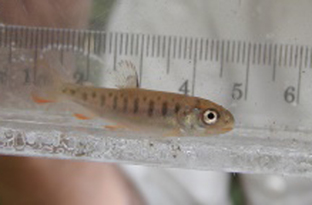

Coho salmon

After hatching, the young fry usually spend one year in coastal streams where they are very competitive for the limited suitable habitat. As smolts they then head out to sea for up to 18 months before returning to spawn in the streams. Although coho are common in small streams along the BC coast, nationally they are an endangered species and their creek and pond habitat is increasingly threatened by development and pollution.

Northwestern Salamander

They have a distinctive gland behind the eye (parotid) that can exude a creamy poison as well as prominent furrows like ribs (costal grooves) on the side between front and hind legs. These large brown broad-headed salamanders are seldom seen, remaining largely in burrows under ground or under debris and large logs. Their sizable egg masses and developing larvae reside in creeks, ponds and wetlands. After 1 or sometimes 2 years, the larvae become terrestrial salamanders, but some individuals retain their gills and stay in the water.

Red legged frog

They breed and lay eggs in shallow ponds, streams and wetlands in the late winter. Unlike Pacific chorus frogs their calls are underwater and seldom heard. Later in the year, adults are seen near moist debris in forests, often near streams or wetlands, feeding on insects and other invertebrates.

Western toad

They lay eggs as distinctive strings, each year in the same areas of shallow shorelines of ponds, lakes, wetlands and slow streams and often with other toads. Toadlets emerge and migrate en-mass. Adults migrate from breeding sites to summer range and then to over-wintering areas. They use burrows for shelter, over a wide range of habitats.

Skunk cabbage

It is also known as swamp lantern. In small creeks and wetlands, the yellow spike florets rise every spring, soon to be overtaken by the plant’s huge basal leaves. The flowers have a pungent smell that attracts the flies that pollinate it and earns the plant its common name. The plant is a favourite early spring food of black bears and the large leaves were used by indigenous peoples in cooking practices.

Maidenhair fern

It has attractive and distinctive circles of delicate fronds. They grace rocky stream banks and forest, often in the spray zone of rapids and waterfalls.

Sitka spruce crop

The stiff needles immediately distinguish Sitka spruce trees from the firs. The thin bark breaks into distinctive scales and the cones are thin scaled and droop from the branches. Huge magnificent trees, often up to 70m, can grow in wet well-drained sites, such as floodplains along river systems.

Some Local Riparian & Creek Ecosystems

Creeks in the Discovery Islands are often small and ephemeral, flowing mainly during the rainy season. They may be found in most linear depressions on all of the islands. Data for creeks provided the basis for some of the initial mapping of Riparian Ecosystems in the DIEM project. DIEM participants can enhance the knowledge of Riparian and Creek ecosystems by obtaining on-site creek-records. Observations of species seen, or the breadth and depth of flowing water in various seasons and times will provide significant records.

Familiar Locations: Sonora Island: Christy Creek, Cortes Island: Whaletown Commons, Quadra Island: Hyacinthe Creek, Read Island: Bird Cove Creek, Maurelle Island: Elephant Bay Creek, Stuart Island: Eagle Creek.